Video: What is irritable bowel syndrome?

This video may take a few moments to load.

(NHS, UK, 2022)

Low or no data? Visit zero.govt.nz, scroll down the page then click on our logo to return to our site and browse for free.

This video may take a few moments to load.

(NHS, UK, 2022)

The exact cause of IBS is still not certain. However, there is emerging evidence that changes in your gut bacteria and inflammation of your immune system may play a role in its development.

In particular, factors that contribute to IBS are thought to be:

The most common symptoms of IBS are abdominal pain or discomfort, often reported as cramping, along with changes in bowel habits.

Usually the pain or discomfort will be associated with at least 2 of the following 3 symptoms:

For a diagnosis of IBS, these symptoms must occur at least 3 times a month.

Other symptoms of IBS may include:

IBS can be triggered by diet and lifestyle, especially stress and anxiety.

Most people with IBS notice that food triggers symptoms. Common trigger foods include:

Additionally, a group of short-chain carbohydrates called FODMAPs(external link) (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols) are also known to trigger symptoms in some people.

If you have the symptoms above, see your healthcare provider for a check-up. See them immediately if have any of the following symptoms:

Your healthcare provider will usually make a diagnosis based on your symptoms. Because the symptoms of IBS are similar to those of more serious conditions, you may have one or more of the following tests:

There is no cure for IBS, but there are treatments that can make a big difference. Talk to your healthcare provider about what might be best for you.

The following approaches help a lot of people to manage their symptoms.

Keep a diary of your symptoms and what you have changed (food or lifestyle). It will help you to see when you are feeling better and when you are feeling worse. Take note of how you felt as well, as feelings like stress and anxiety can affect your symptoms.

Eat a variety of foods from the 4 food groups. Learn more about the 4 food groups and healthy eating.

Certain foods are known to make symptoms worse.

For diarrhoea:

For constipation:

For reflux/indigestion:

Researchers have also found that reducing your stress can help to ease your symptoms. Read more about stress and how to manage it.

There is evidence that being more active can help reduce your IBS symptoms. This may be because it helps digested food move through your gut, reducing gas and bloating. Read more about the benefits of physical activity.

Because of the connection between the brain and the gut (the gut-brain axis), talking therapy such as CBT, has been found to be helpful in managing IBS symptoms.

There is strong evidence to suggest that gut-directed hypnotherapy improves symptoms in people with IBS by 70-80%, which is as equally effective as the low FODMAP diet and there are no restrictive diets to follow. There are clinics that offer this in person, however a lower cost option are apps such as Nerva(external link), a 6 week programme developed by a gastroenterologist at Monash University.

Probiotics are live, beneficial bacteria found in fermented foods like yoghurt, kefir and tempeh or in pill form. The evidence to support the use of probiotics in IBS is inconclusive, there is some evidence behind certain strains so it’s best to speak to a dietitian.

Probiotics may be beneficial for some people, but in others they may increase wind and bloating.

If you want to trial a probiotic, it’s recommended you start slowly and try for a minimum of 4 weeks. If you don’t notice a change, or have an increase in your symptoms, stop taking them.

If you have tried all of the above tips and your symptoms don’t improve, it is recommended that you see a dietitian to follow a short-term low-FODMAP diet followed by a reintroduction phase.

Research suggests that 3 in 4 people with IBS get symptom relief, usually within 1–4 weeks, from following a low-FODMAP diet. These positive effects can continue long term. It’s best if you can see a dietitian experienced in this diet to help support you make the changes needed.

FODMAPs are either poorly absorbed in your small intestine or are not digestible.

Because they are poorly absorbed, they reach the end of your digestive system (the large intestine or colon), where most of your gut bacteria live. Here, your gut bacteria ferment them, producing gas. This leads to bloating and flatulence.

FODMAPS also have an osmotic effect, which means they draw water into your colon (bowel). This can cause cramping and more bloating.

Depending on your digestive system, the combination of producing gas and drawing water in can lead to inconsistent or excessive bowel movements, diarrhoea or constipation, and tummy pain.

This process is likely to be made worse by stress and lack of physical activity.

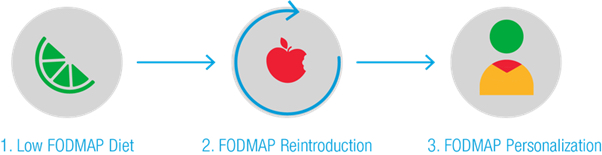

Read more about common foods containing FODMAPs(external link). There is also an app developed by Monash University to help you follow this diet. It is important that after a period of 4–6 weeks of a low FODMAP diet you start to reintroduce foods that contain FODMAPs so that you don’t have a lifetime of restricted eating and can enjoy a variety of foods.

It is strongly recommended that you get support from a dietitian throughout this process, as it is important to follow the diet correctly and to ensure you are still getting a balanced diet.

The following video provides a tour of the Monash University FODMAP diet app. This video may take a few moments to load.

(Monash University, 2022)

Many dietitians and doctors now recommend a low-FODMAP diet as a key part of a treatment plan for people with IBS.

Most people with IBS who have tried the diet have experienced a great improvement in their symptoms and a reduced need for medication.

Some foods can cause your bowel to stretch and expand. This usually happens because they contain elements that:

FODMAPs are the most common food element this happens with. They are fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates or 'sugars'. They can't be digested by your body but are easily fermented by bacteria once they reach your bowel.

FODMAPs stands for:

If this seems too complex – just remember that 'saccharide' is a different word for sugar. Polyols are sugar alcohols — meaning sugar molecules that have an alcohol side-chain attached. You might already know some of these sugars or have seen them in ingredients lists on food packaging.

Common FODMAPs include:

*This table is not an exhaustive list of high and low FODMAP foods. For a comprehensive database of FODMAP food information, see the Monash University FODMAP Diet App or High and low-FODMAP foods(external link), Monash University, Australia.

The goal of a low-FODMAP diet is usually to remove the problem foods and then slowly reintroduce them over time. Carry out any changes to your diet with help from your doctor or a dietitian.

You don't need to cut out all FODMAPs for life. Removing food groups from your diet can result in nutrient deficiencies.

Source: Starting the low-FODMAP diet(external link) Monash University, Australia

Watch a video about the 3 phases of the FODMAP diet and some helpful tips. This video may take a few moments to load.

(A Little Bit Yummy, 2023)

More videos about FODMAP and IBS can be found on the A Little Bit Yummy YouTube channel(external link).

Low FODMAP smartphone app(external link) Monash University, Australia, 2015

Starting the low-FODMAP diet(external link) Monash University, Australia

A little Bit Yummy(external link) YouTube channel

A Little Bit Yummy(external link) FODMAP made easy (paid membership)

There are medicines that can help with some symptoms of IBS such as pain, constipation or diarrhoea. Medicines can help to control the severity of the symptoms but do not reverse or “cure” them.

Each person with IBS will have different symptoms and medicines are aimed at easing your most troublesome symptom or combination of symptoms.

Ask your doctor or nurse for dietary advice; many people with IBS find that certain foods such as FODMAPS can trigger symptoms and following a low-FODMAP diet can be beneficial.

Medicines that relax the stomach (tummy) muscles can be used to used to relieve tummy cramps or spasm-type pain that can occur with IBS. They can also help to ease bloating. These medicines are called anti-spasmodics.

Examples of anti-spasmodics include hyoscine tablets (Buscopan® or Buscopan Forte®) and mebeverine (Colofac®).

Your doctor may recommend a 1 week trial of taking these regularly. If they work, then you may be advised to use them as required, when the symptoms arise. Read more about hyoscine tablets and mebeverine.

There is some evidence that peppermint oil may be useful for bloating, wind and bowel cramps. However, in some people, peppermint oil can cause or worsen reflux (indigestion).

In New Zealand, peppermint oil is available as capsules (Mintec® and Colpermin®).

Your doctor may recommend a trial of 1 capsule 3 times daily 30–60 minutes before meals for 2 weeks. If it's helpful, you can continue taking these, but reduce to the lowest effective dose. Ask your pharmacist for advice on how to take peppermint oil capsules.

If your main symptom is constipation, laxatives may help. There are a variety of different laxatives which work in different ways. Some laxatives can cause bloating, flatulence and discomfort, which can make your IBS worse. Your doctor or pharmacist can advise you on the best laxative for you. You may need to try a few laxatives before you find the right one for you. Read more about laxatives.

If diarrhoea (runny poos) is your main problem, medicines such as loperamide may be helpful to increase stool firmness, decrease stool frequency and reduce urgency. This can be used in combination with an anti-spasmodic such as mebeverine.

Loperamide works by slowing the movement of the gut, and in this way reduces the number of bowel motions and firms up runny poos.

Your doctor will start you on a low dose and depending on your symptoms, may increase your dose gradually. Do not take more than 8 tablets in 24 hours.

An approach that has been suggested for people who are fearful of the sudden and urgent need to defaecate (poo) that can occur with IBS, is for them to take 2–4 mg of loperamide approximately 45 minutes before leaving their house, particularly if access to a toilet is limited, such as when shopping or exercising.

Note that additional doses need to be carefully managed to avoid constipation later in the day. Discuss the best options with your doctor or pharmacist.

Another medicine that may be used for diarrhoea associated with IBS is mebeverine. Read more about loperamide and mebeverine.

Antidepressants

Some people may be started on a trial of antidepressants such as amitriptyline or nortriptyline. These are used to relieve pain and slow movement of the gut, rather than treatment of psychological symptoms.

You will be started on a low dose and if needed, your dose will be increased only after 3 to 4 weeks. Amitriptyline or nortriptyline may not be suitable if you also have constipation. Read more about amitriptyline and nortriptyline.

Probiotics

The evidence to support the use of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome is inconclusive (not clearly for or against their use). A 4-week trial of probiotics in the form of yoghurts or other fermented milk products can be considered. However, some of these products also contain ingredients that may worsen IBS symptoms, such as fructans, fructose or lactose. Read more about probiotics.

IBS Central(external link) Monash University, Australia

IBS resources(external link) Monash University, Australia

A Little Bit Yummy(external link) FODMAP made easy (paid membership)

Strategies for managing IBS - FODMAP and beyond(external link) A Little Bit Yummy, NZ

Three phases of the low FODMAP diet chat session(external link) A Little Bit Yummy, NZ

FODMAP Stacking - FODMAP Chat Session with Monash University(external link) A Little Bit Yummy, NZ

More videos can be seen on the A Little Bit Yummy(external link) site.

Trouble going to the loo? [PDF, 1.1 MB] Healthify He Puna Waiora, NZ

Common foods containing FODMAPs(external link) Health Food Media, NZ

Monash University low FODMAP diet guide(external link) Monash University, Australia

Further investigation – colonoscopy results(external link) Health Ed, NZ

Telehealth clinical module – abdominal assessment(external link) ProCare, NZ, 2022

Simplifying IBS – targeted management that isn’t just FODMAPS(external link) (Goodfellow Unit Webinar, NZ, 2020)

Irritable bowel syndrome by Dr Adele Melton(external link) (The Goodfellow Unit, NZ, 2018)

Functional GI disorders – Dr Anne Tait (29 minutes)(external link) (PHARMAC, NZ, 2020)

Treating IBS(external link) Monash University, Australia

Irritable bowel syndrome – new and emerging treatments(external link) BMJ Learning, 2015

Health Food Media, NZ

Monash University, Australia

Healthify He Puna Waiora and Mediboard, 2023

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Dr Derek JY Luo, MBChB (Otago) FRACP, Consultant Gastroenterologist; Gabrielle Orr & Amanda Buhaets, NZ Registered Dietitians, Auckland

Last reviewed:

Page last updated: