All operations carry some risk. Talk to your surgeon so you understand what's involved and are aware of any complications you may face. The following are some possible complications.

Bleeding and infection

Any operation that involves cutting has the risk of bleeding or infection. The possibility of needing a blood transfusion will be discussed with you before the operation. Antibiotics are often used at the beginning of the operation to decrease the chances of an infection afterwards.

Anaesthetic complications

Modern anaesthetics are very safe. Although it's rare, some people can have reactions to the anaesthetic medicines. Before your operation, it's likely you'll have an appointment with the anaesthetist who will be looking after you during the surgery. They will discuss the type of anaesthesia you will be receiving and the risks associated with this.

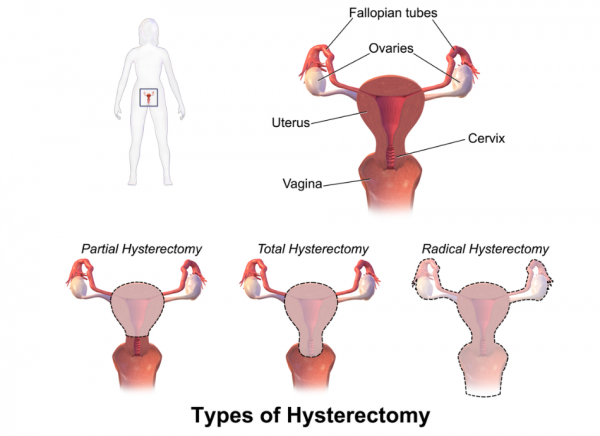

Damage to surrounding organs

Your uterus is surrounded by other organs, which need to be gently pushed aside so the surgeon can operate. Endometriosis, infection and cancer can cause your bladder or bowel to become stuck to your uterus, ovaries or fallopian tubes. The surgeon needs to be very careful in these situations to make sure these organs are not damaged. The chance of problems like this happening in other situations is very low.

After the operation

You will usually stay in hospital for 2–4 days and go home only after your bladder and bowels are working properly and any pain is managed.

When you get home, it can be easy to overdo things, so it's important to rest as much as possible. Resting also decreases the chance of getting an infection in your wound.

You shouldn't drive for at least 24 hours after an anaesthetic. Some insurance companies won't let you drive for 4–6 weeks after an abdominal hysterectomy. Others may require your healthcare provider to say you are okay to drive. To drive safely you need to be able to sit in the car comfortably, make an emergency stop, wear your seatbelt and look over your shoulder to park.

If you have stitches, these will usually stay in place for about a week.

Avoid having sexual intercourse for about 4–6 weeks to allow the scar inside to heal properly. It's also important not to put anything in your vagina during this time - including a penis, fingers, sex toys, tampons, or douches. If sex is still uncomfortable after a couple of months, talk to your healthcare provider.