Low or no data? Visit zero.govt.nz, scroll down the page then click on our logo to return to our site and browse for free.

Dementia | Mate wareware

Key points about dementia

- Dementia (mate wareware) is a term used to describe symptoms that occur when there is a decline in brain function.

- This may include problems with memory, thinking, behaviour and the ability to perform daily tasks.

- If you're becoming increasingly forgetful, particularly if you're over the age of 65, it may be a good idea to talk to your GP about the early signs of dementia.

- An early diagnosis can help you to get the most benefit from treatment.

- Dementia is more common in people over 65, but it is not a normal part of ageing.

- Treatment depends on the symptoms, diagnosis and cause of the dementia.

Dementia describes a group of related symptoms resulting from an ongoing decline of your brain.

It may include problems with:

- memory

- thinking speed

- language

- understanding.

As these symptoms progressively get worse, they can make it difficult for you to carry out your normal daily activities.

- Dementia occurs as a result of damage to brain cells. The symptoms that develop depend on the areas of your brain that have been damaged. It is progressive, meaning the symptoms gradually get worse over time.

- Dementia is more common in people over 65, but it is not a normal part of ageing. Māori and Pasifika people have higher rates of dementia than Pākehā. In te reo Māori, dementia is known as mate wareware.

- There are a number of different types of dementia. The most common is Alzheimer’s disease.

- Treatment depends on the symptoms, diagnosis and cause of the dementia. Medication cannot cure dementia or repair brain damage. However, it may improve symptoms or slow down the disease for a short period of time.

- An early diagnosis can help you to get the most benefit from treatment. It also helps you to plan for the future and get the right support and advice.

There are a number of different types of dementia. The most common is Alzheimer’s disease, which affects about 60% of people with dementia. Other types of dementia are vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia and fronto-temporal dementia. You may also be diagnosed with have ‘mixed’ dementia, eg, a mixture of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

Early onset dementia (or young onset dementia) describes dementia that occurs in people under 65 years of age. About 5% of people who develop dementia have early onset dementia.

Dementia is due to damage and eventual death of cells in the brain. This may be caused by injury, damage to your brain's blood vessels from diabetes, smoking or a stroke, or damage from toxins such as alcohol. Once cells die, they are not replaced.

Most dementia is not inherited. However, in rarer types of dementia there may be a strong genetic link, but these are only a tiny proportion of overall cases of dementia.

The older you are, the greater your chance of getting dementia. Most people are over 65 when diagnosed, although some younger people have early onset dementia.

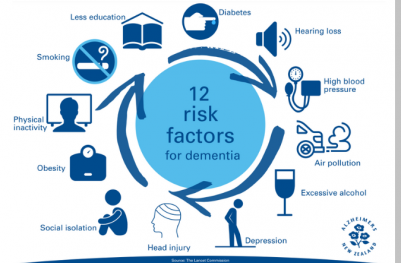

There are some groups of people who are known to have a higher risk of developing dementia. These include people with:

- Down syndrome or other learning disabilities

- Parkinson's disease

- risk factors for cardiovascular disease (such as angina, heart attack, stroke and peripheral arterial disease)

- a history of drinking excess alcohol

- a family history of dementia

- a history of a head injury

- mental health conditions such as schizophrenia or severe depression

- low physical activity levels.

Image credit: Alzheimers NZ

Dementia symptoms affect 3 main areas:

- mental ability

- mood, personality and behaviour

- day-to-day activities.

So symptoms usually include forgetting things, repeating questions, not remembering appointments, forgetting people’s names, forgetting the names of objects, not being able to plan the steps to do everyday tasks such as making a meal.

If you or someone you care for are becoming increasingly forgetful, it may be a good idea to talk to your GP about the early signs of dementia. Your doctor will do some simple memory tests and refer you for further assessment if needed.

Getting an early diagnosis can be a great help. Knowing what is going on means you will be able to plan ahead and get the support you need.

Although there is no cure for dementia, there are a number of treatments, including:

- lifestyle changes

- cognitive stimulation therapy

- treating heart risk factors

- medication

- mind and memory-based activities.

Lifestyle changes

There's no sure way to prevent dementia, but there are steps you can take that might help. Including the following in your day-to-day might be beneficial:

- getting regular exercise

- avoiding or reducing alcohol and other substance use

- eating a healthy diet

- getting enough sleep.

Treat heart risk factors

Management of heart risk factors may benefit all types of dementia. Generally, what is good for your heart is good for your brain. Read about heart risk assessment.

Whānau support

Māori understandings of mate wareware differ from the main Western conceptions of dementia. Whānau are generally inclusive of their whānau member’s changes in their daily functioning and new emerging behaviours. Whānau are crucial for the care of a kaumātua (older person) with mate wareware, so they need to be included in treatment discussions and decisions, along with the person with mate wareware.

Te oranga wairua (spiritual wellbeing) has been identified as central to Māori thinking about health, and effective care for someone with mate wareware must therefore include cultural practices to strengthen wairua of the whole whānau.

Read more about understanding and learning about mate wareware from a Māori perspective.(external link)

Medication

There are medicines that can help some people with the symptoms of forgetfulness and improve their ability to think more clearly in the earlier stages. Medicines do not cure dementia and they may only work for some people. The aims of treatment are to promote independence, maintain function and treat symptoms. These medicines fall into 2 categories:

- cholinesterase inhibitors (such as donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine)

- memantine.

These work by enhancing the levels of a chemical in the brain (called acetylcholine), that is involved in memory and judgment. Read more about medicines for dementia.

Your doctor will also review any other medicines you are taking to check that they are not contributing to any dementia-like symptoms.

Mind and memory-based activities

These could include:

- cognitive rehabilitation, where a health professional helps you achieve a goal such as learning to use a mobile phone

- life story work, where you use a scrapbook, photo album or electronic app to remember and record details of your life

- music and creative arts therapies to keep your brain active and help you express your emotions

- complementary therapies such as aromatherapy, massage or bright light stimulation – discuss these with your doctor beforehand

- doing brain exercises and practicing memory strategies.

Cognitive stimulation therapy

Cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) is a structured group treatment developed for people with mild to moderate dementia. It consists of 14 sessions with a range of activities and discussions aimed at general enhancement of mental and social functioning. The sessions actively engage people with dementia, providing an optimal learning environment and the social benefits of being part of a group. CST has been found to be an acceptable psychological therapy for older people with a clinical diagnosis of mild to moderate dementia.

Care planning meeting

Plan ahead so that you have more say in your future. Arrange a meeting (or get someone else to do it) with all the people involved in your care. This may include your carer, family/whānau members, or your practice nurse or GP.

Agree on a care plan to support you to stay as well as possible for as long as possible. This might include:

- having a driving assessment

- arranging enduring power of attorney

- writing or updating your will

- developing an advance care plan

- accessing services to help you stay independent for as long as possible

- learning about your condition.

Having a driving assessment

Driving requires quick reflexes and decision making. Having a driving assessment will help you work out whether it is safe for you to continue driving for now, and if not, how you will manage without driving. Read more about dementia and driving.

Arranging enduring power of attorney

Having an Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA) means you can have peace of mind that you have decided, ahead of time, who you trust to make decisions for you if you can’t decide for yourself. Read more about enduring power of attorney.

Writing or updating your will

A will sets out your wishes in terms of who to leave your possessions and money to and states who you would like to carry out your wishes. It can include special instructions for a funeral. If you don’t have a will, it could also put your family into legal and financial difficulties. Learn more about making a will.(external link)(external link)

Developing an advance care plan

An advance care plan is a way to record your wishes in terms of current and future medical care. It is an ongoing process of talking with those closest to you and getting information to help you make decisions about your care. It can include end of life planning. Read more about advance care planning.

Accessing services

Find out about services early on that can help you and help your carer to support you. Start with a free half hour consultation with an Alzheimer's NZ senior trustee at the Public Trust. This is available to discuss things that are related to estate planning. Freephone 0800 156 015 to book.

Westpac offers dementia friendly banking.(external link)(external link)

Learning about your condition

Learning about dementia can help you plan for the future as well as stay independent for as long as possible. See these resources and videos and other links under Learn more below.

People with dementia can easily become socially isolated which is hard for them and for their carers. Keeping them active and taking part in the right activities for them is important for their wellbeing, and in some cases can help slow the progression of the disease.

Here are some things to consider when planning activities:

- Think about the setting – Avoid noisy places, big crowds or places with lots of movement as this can make people with dementia feel nervous, unsure and sometimes upset. Find an activity that has a good balance between calmness and stimulation so that they are engaged without feeling overwhelmed.

- Keep up their previous interests – A person with dementia is still the same person they once were, despite changes in their memory and behaviour. Try an activity they used to like doing or were interested in. Taking part in something familiar that they used to enjoy can make them feel happy. It may even reignite some memories. For example, if they loved walking, go for a walk on the beach or at a park, or if they loved art, join an art class with people their age. Remember, what’s important is enjoying the moment, even if they can’t remember it later.

- Make them feel useful – Doing something that reinforces a past role or enables them to achieve something physically is beneficial. For example, folding or hanging out the washing provides a sense of achievement and encourages family bonds. Focus on doing 1 task at a time and break it down into manageable steps.

- Take your time – Don’t rush a person living with dementia. Don’t focus on completing an activity or finishing something, just enjoy the process of getting involved and taking part. If the person feels under pressure, it may put them off and stop them from giving something a go.

A wide range of support organisations and services is there to help you.

Phone support 0800 004 001 Alzheimers NZ(external link)(external link)

- Find your local Alzheimer's branch(external link)(external link) NZ

- Dementia NZ (external link)(external link)

- Dementia Auckland(external link)(external link)

- NZ Dementia Foundation (external link)(external link)

- Carers NZ(external link)(external link) 0800 777 797

- More dementia support groups

- Eldernet(external link)(external link) Information service on issues affecting older New Zealanders

- Seniorline(external link)(external link) Information on how to get help at home, community services and rest homes

See our page For carers of people with dementia.

Video: Memories and forgetfulness – Colin's story

This video may take a few moments to load.

(Alzheimers NZ, 2016)

Video: Growing up with dementia – Enzo's story

This video may take a few moments to load.

(Alzheimers NZ, 2016)

Video: Conversations about dementia – Kerry's story

This video may take a few moments to load.

(Alzheimers NZ, 2016)

Video: The penny drops – Tania's story

This video may take a few moments to load.

(Alzheimers NZ, 2016)

Video: Yep, my dad has dementia – Victoria's story

This video may take a few moments to load.

(Alzheimers NZ, 2016)

Video: The unspoken impact of dementia

This video may take a few moments to load.

(Alzheimer's Australia, 2014)

Video: Man in nursing home reacts to hearing music from his era

Henry seemingly comes alive when he hears music from his era. Music and art can be very beneficial to people with dementia. This video may take a few moments to load.

(Music and Memory, US, 2011)

Video: Stan & Denise Lintern – dementia

Family man Stan Lintern was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in 1996 after a long career in the NHS (National Health Service in the UK). This video may take a few moments to load.

(Alzheimer's Society, UK, 2011)

Video: MiniDoc: together apart

Two out of three New Zealanders are affected by dementia. Family members become carers as they watch the disease slowly take their loved ones. Filmmaker, Suzi Jowsey, bravely follows her own family’s tough journey of caring for their mum who has Alzheimer’s. This video may take a few moments to load.

(AttitudeLive, NZ, 2015)

Video: The unexpected positives of dementia | 'My story hasn't ended...only the ending has changed'

This video may take a few moments to load.

(Alzheimer's Australia, 2014)

Alzheimer's disease

Dementia – for carers

Information for carers on managing disruptive behaviour

Driving and dementia

Dementia – preventing social isolation

Reducing your risk of dementia

Ageing – what is normal and when to seek medical advice

Advance care planning

Enduring power of attorney

Mini-ACE

Dementia topics | Mate wareware

Understanding mate wareware from a Māori perspective(external link)(external link) Mate wareware, NZ

Information and support(external link)(external link) Alzheimer's NZ

Information sheets(external link)(external link) Dementia NZ

About dementia(external link)(external link) Dementia Australia

Dementia(external link)(external link) NHS Choices, UK, 2017

Scared but not prepared – dementia survey(external link)(external link) Public Trust, NZ, 2019

Dementia and the Arts: Sharing Practice, Developing Understanding and Enhancing Lives(external link)(external link) Future Learn Online Course (paid) 2 hours a week for 4 weeks

Resources

A variety of Information sheets (external link)from Dementia NZ

Resources and information on dementia for New Zealanders(external link)

A variety of factsheets(external link) from Alzheimer's NZ

About dementia(external link)(external link) Alzheimers NZ, 2019

Safer walking(external link)(external link) Alzheimers NZ, 2019

Living well with dementia(external link)(external link) Alzheimers NZ, 2016

Supporting a person with dementia(external link)(external link) Alzheimers NZ, 2021

Understanding changed behaviour(external link)(external link) Alzheimers NZ, 2016

The later stages of dementia and end of life care(external link)(external link) Alzheimers NZ, 2016

Transitioning to residential care(external link)(external link) Alzheimers NZ, 2016

What is dementia?(external link) Dementia New Zealand

Getting a diagnosis of dementia(external link) Dementia New Zealand, 2022

Information for friends and family(external link) Dementia New Zealand, 2023

Frontotemporal dementia(external link) Dementia New Zealand

Disinhibited behaviours(external link) Dementia New Zealand

Dementia and driving(external link) NZ Transport Agency, 2018

Younger onset dementia – a practical guide Alzheimer's Australia, 2009

Your guide to coping with Alzheimer’s and dementia (external link)Home Instead Senior Care, US

Dementia in multiple languages(external link) Health Translation Australia

References

- Memory loss and dementia(external link)(external link) Patient Info, UK, 2017

- Can dementia be prevented?(external link)(external link) NHS, UK, 2017

- Cognitive stimulation therapy – a New Zealand pilot(external link)(external link) Te Pou, NZ, 2014

- The dementia guide(external link)(external link) Alzheimer’s Society, UK, 2017

- Dudley M, Menzies O, Elder H, Nathan L, Garrett N, Wilson D. Mate wareware – understanding ‘dementia’ from a Māori perspective(external link) NZ Med J. 2019;4;132(1503).

- Is dementia hereditary?(external link) Alzheimer's Society, UK

See our page Dementia for healthcare providers

Brochures

Alzheimers NZ, 2019

Alzheimers NZ, 2016

Alzheimers NZ, 2021

Credits: Healthify editorial team. Healthify is brought to you by Health Navigator Charitable Trust.

Reviewed by: Dr Helen Kenealy, geriatrician and general physician, CMDHB

Last reviewed:

Page last updated: