Cultural safety focuses on the patient. It provides space for patients to be involved in decision making about their own care and contribute to the achievement of positive health outcomes and experiences.

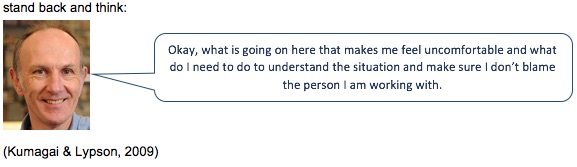

In October 2019, the Medical Council of New Zealand published a statement on cultural safety. The key points in the statement were as follows:

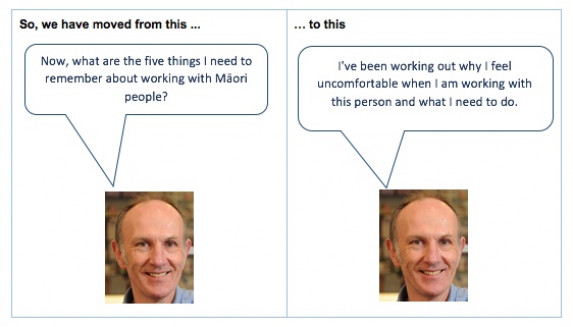

- Cultural safety focuses on the patient experience to define and improve the quality of care. It involves doctors reflecting on their own views and biases and how these could affect their decision making and health outcomes for the patient.

- The Medical Council has previously defined cultural competence as “a doctor has the attitudes, skills and knowledge needed to function effectively and respectfully when working with and treating people of different cultural backgrounds”. While it is important, cultural competence is not enough to improve health outcomes, although it may contribute to delivering culturally safe care.

- Evidence shows that a competence-based approach alone will not deliver improvements in health equity.

- Doctors inherently hold the power in the doctor-patient relationship and should consider how this affects both the way they engage with the patient and the way the patient receives their care. This is part of culturally safe practice.

- Cultural safety provides patients with the power to comment on practices, be involved in decision making about their own care, and contribute to the achievement of positive health outcomes and experiences. This engages patients and whānau in their health care.

- Developing cultural safety is expected to provide benefits for patients and communities across multiple cultural dimensions which may include Indigenous status, age or generation, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, religious or spiritual belief and disability1. In Aotearoa / New Zealand, cultural safety is of particular importance in the attainment of equitable health outcomes for Māori.

Statement on cultural safety Medical Council, NZ, 2019

While the Medical Council’s statement only refers to doctors, the statements apply equally to all healthcare staff. Working in health care in New Zealand means healthcare staff need to develop and provide culturally safe patient-centred care.

What cultural safety is not

Sometimes it is easier to say what cultural safety is not.

| Not cultural safety | Reasons |

|---|---|

| Treating everyone the same | People are never the same, even if they are all Māori, Samoan or English. Treating everyone the same makes health inequities worse, not better. |

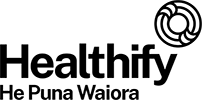

| A checklist | There is no list of things to do when you visit a Māori whānau. |

| Learning about other cultures | This encourages assumptions, as the health coach is saying they can know about their own culture as well as other cultures. |

| Coming from the same ethnic group | Just because the health coach is Māori and the person they are coaching is Māori is no guarantee that the health coach will give culturally safe care. |

| Speaking the same first language | This is similar to the last one. The health coach and the person they are coaching might both be speaking English but that is no guarantee that the person will get culturally safe care. |

| Using words that suggest the person is to blame, eg, non-adherent, non-compliant, at risk, target group, has low health literacy | Using these sorts of words means we have automatically blamed the person, rather than tried to understand all the reasons why the person is not taking their medicines, eg, money, side effects, other priorities. |

Why is cultural safety important?

Because culture impacts on care, healthcare staff need to be aware of cultural diversity and learn to function effectively and respectfully when working with and treating people of different cultural backgrounds. This includes cultural dimensions such as age, gender, sexual orientation, religious or spiritual beliefs and a focus on improving health outcomes for Māori as tangata whenua.

Cultural safety helps to address the inequities (lack of fairness) in the healthcare system. For example, there is a lot of information that shows Māori and Pasifika peoples have much worse health outcomes than other population groups, especially Pākehā.

Cultural competence is one way of addressing those inequities that are caused by:

- the design of the health system

- prejudice by healthcare providers and healthcare professionals, eg, beliefs that different groups are not as able, motivated or keen to be as healthy as other groups such as Pākehā

- discrimination by healthcare providers and healthcare professionals, eg, actions such as not referring Māori people to rehabilitation programmes.

Dr Elana Curtis and colleagues from The University of Auckland have written an article about why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity. (external link)