Image credit: Healthify

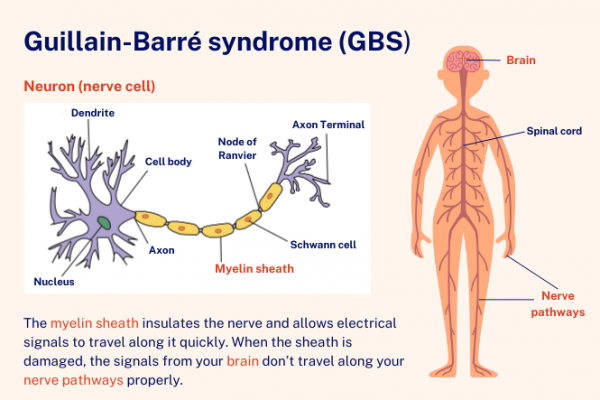

Guillain-Barré syndrome happens when your immune system attacks and damages your peripheral nerves. Your peripheral nerves are the nerves in your body, arms and legs – the ones outside your brain and spinal cord. Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a group of similar diseases affecting different parts of different nerves. The commonest ones are:

- Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP): This is the most common form. Your immune system attacks the myelin sheath, which is a fatty layer around the nerve that makes the electrical signal travel faster.

- Acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN) and acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN): Your immune system attacks the nerve itself, called the axon.

Video: Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) 101

The video below gives an overview of GBS, how it affects you, its treatment and recovery. It may take a few moments to load.

(GBS-CIDP Foundation International, US, 2015)